Q Magazine 1997

By Mark Blake

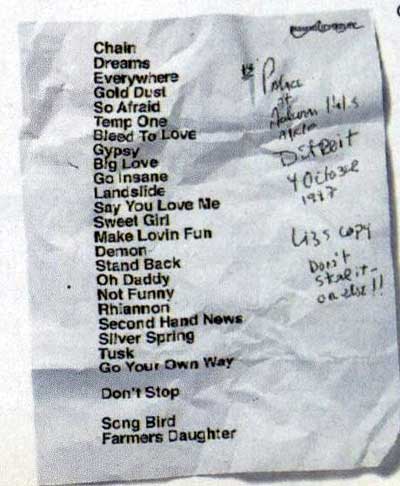

PALACE AT UBURN HILLS, MICHICAN

October 4, 1997

The banner is still visible in the 10th row of this 16,000-seat basketball arena: "My name is Rhiannon. I am five years old and I love Fleetwood Mac!" Judging by the fact that if flutters above the heads of the audience, it's unlikely that the bearer is the five-year-old Rhiannon herself. Nevertheless, the sentiment is clear. For one couple here, Fleetwood Mac were such a defining presence in their lives that they had to name their child after one of the band's songs. For one segment of the American populace, the reunion of this particular incarnation of Fleetwood Mac (the commercially lucrative one: Mick Fleetwood, John and Christine McVie, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks) is a serious affair.

Rhiannon, the song, shows up late in a 150-minute set. By then the heartstrings of this partisan throng have already been tugged by the fluid, tuneful Dreams, Landslide and Gypsy, just what the audience of fortysomethings and their offspring, eager to see their folks favourite band, expect. The hangar-like sports hall is located in a sprawl of greenery, an hour's drive north of Detroit. Aside from the West Coast with which they were so closely identified, if is there far-flung corners of the American heartland that is Fleetwood Mac country.

Three weeks into the tour and the band's new album, The Dance, a recording of their reunion concert for MTV, is still nestling in the Billboard Top 5. The last Fleetwood Mac album, Time, in 1995, recorded with sole survivors Fleetwood and John McVie, failed to enter the American charts. Humiliated, they threw in the towel.

Cynicism dictates a cautious approach to such get-togethers, but as the band deliver their opening gambit, The Chain, replete with Buckingham's almost comically brilliant guitar workout, only the most unforgiving could find fault. As Buckingham notices later with rascally glee, "Sure, go ahead, talk about the money, but there's an emotional resonance to what we're doing in these shows that you won't have got from The Eagles," whose Don Henley serenade Nicks, Buckingham's ex.

The emotional resonance was always a selling point, especially on 1977's 23-million-shifting Rumours, recorded while Buckingham and Nicks's relationship crumbled, the McVie marriage fell apart and Fleetwood's wife sloped off with his best friend. Inevitably, the set draws largely from this album and the four others recorded by this line-up between 1978 and 1987. And what a curious line-up it is: Fleetwood, implausibly tall and decked out in a pantomime pirate's outfit; McVie, his hangdog, sad-eyed bass-playing partner; ex-wife Christine, charmingly posh, like a minor royal in velvet leggings; Buckingham, serious, undeniably gifted and very Californian ('My lawyers and manager both signified that this tour could be a good move for me in the long term') and Nicks, mid-'70s uberbabe, mid-'80s solo superstar, and perhaps the only 49-year-old woman with the gall to appear on stage wearing platform heels high enough to give Ginger Spice vertigo.

It is Nicks to whom the audience warm most, her faintly ludicrous routine of tambourine pounding and pirouettes egging them into mild hysteria. Yet when she husks her way through Gold Dust Woman, a spooky homage to the cocaine that, in the word of Buckingham, 'rendered us bleary-eyed for a long time' , her act's sometimes pantomime showiness is upstaged by the eerie quality of her voice.

Offstage, all five seen surprised, amused and even a little embarrassed about working together again.

"The music is easy," states Nicks earnestly. "It's the other stuff that's hard. But I realised a long time ago that there is no Fleetwood Mac without Lindsey. If it can't be with him, then let's not do it."

The "we all love each other" party line may be trotted out once too often, but Nicks's platitudes are not completely misguided. Buckingham remains the band's musical linchpin; instilling a touch of barely-controlled mania into the jerky, angular 1979 hit single Tusk ("Back then I really wanted to be in The Clash," he will confess later) and playing the tetchy, demanding musical foul to the more melodic Nicks and Christine McVie. It's little wonder the band foundered without him.

Go Your Own Way sees out the main set, Buckingham and Nicks once American rock's most beautiful couple, all too quickly a grudge match in cheesecloth and flares ham it up, trading knowing looks and even returning to the stage holding hands.

"Sure, we're playing it out," admits Buckingham, looking faintly appalled. 'But when I quit the band, Stevie and I still had unresolved issues. It's kinda nice to be getting along again.'

After the show, the general consensus of opinion seems to be that the show flagged a little. John McVie confesses to 'sluggishness', while Nicks grumbles that it was too long. To the onlooker though, there's nothing that couldn't be rectified by judicious pruning and a tweak of the set list. Buckingham's solo spot, including a pared-down Big Love, is superb; the group's parting shot of Brian Wilson's The Farmer's Daughter understated and effective.

Cosseted by a 150-strong staff, including no less than seven fractious managers, the saga of this oddball gathering of ex-wives and husbands continues to play in the manner of what Christine McVie freely describes as �a mini-soap opera�.

"America wants a happy ending to the fairy story," she laughs. 'I'm sure there were people out there tonight who genuinely believe that Stevie and Lindsey will be reunited, and everything will be alright again. Let me say now that will never happen."

Ms McVie seems the least likely to entertain anything more permanent.

"I'm moving back to England soon, Kent actually," she says, cheerily. "What I really want to do is open a restaurant."

This odd gathering of five wildly different individuals is never more evident than back at the band's hotel after the show. Having emerged from a limousine, John McVie ambles into the lobby and heads straight for the bar where he will hold court, tipsy but touchingly affable, for the next two hours ("My ex-wife's a luverly, luverly lady, even though she told me to fuck off," he informs no one in particular).

In contrast, Stevie Nicks's arrival is heralded by six handmaidens, who huddle around their mistress before hustling her in a pincer-like movement towards the waiting lift.

"Christ knows why this band works but it does," avers Fleetwood. "Lindsey asked me and John to work on his solo album and it just took off from there. I wanted it to happen, but I didn't dare ask for almost a year. We're survivors. Being in this band is like going to that Gordonstoun school in Scotland that fucked Prince Charles up."

Older, wise and straighter, "I've been clean for seven years" Fleetwood is adamant that he won't force anyone into a more permanent commitment.

"If we go to Europe, great. If we split up at Christmas, that's fine too. Let's be dignified about it."

Yet there's still a nagging feeling that for him and McVie, there is no life without Fleetwood Mac.

"John asked me the other day, What are we going to do when this is all over?" he shrugs, before outlining a remarkably detailed game plan to get ex-Fleetwood Mac guitarist Peter Green's solo career back on track. "I'd love to help him," he whispers, with a conspiratorial wink.

"It's working at the moment," concedes Buckingham. "But there have already been times when I'm up there hammering away and I start thinking, Jesus, How did I end up back here?"

With three excellent but largely unsuccessful solo albums to his name Buckingham admits the reunion might help him sell a few more of his own records next time around. "That's, er, kinda the idea," he confesses, nervously.

The next evening's gig is in Indianapolis and in the morning there's a private plane waiting at a nearby airstrip. Limousines pull up kerbside; Nicks's entourage usher her into lobby; a clearly hungover John McVie re-appears.

"Y'know before Lindsey and I joined we had to steal ourselves not to go into stores," recalls Nicks, stepping into the stretchiest of limousines. "Six months later we were earning $400 a week each and I was totally famous. We used to pin $100 bills up on the walls of our apartment just for fun. You go through that with someone, you do'�t forget."

At the airstrip she follows her former other half into the plane. Strangely, this time they don't hold hands.