|

|

|

|

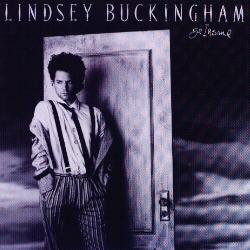

This site is dedicated to the much under valued LINDSEY BUCKINGHAM, the architect of Fleetwood Mac's Rumours era sound and creator of three magnificent solo albums |

||

|

|

||

|

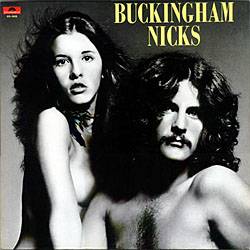

It only seems like Fleetwood Mac has been making hit records forever. In fact, it was just five years ago that the one-time English blues band, rejuvenated by the addition of Californians Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, virtually took over American radio with the smash album Fleetwood Mac, which yielded the hit singles "Rhiannon," "Say You Love Me," "Over My Head" and "Monday Morning." And as astonishing as that albumís success was, no one could have been prepared for what happened when the groupís next LP, Rumours, came out in 1977. Behind the strength of hits like "Second Hand News," "Dreams," "Go Your Own Way" and "Donít Stop," Rumours became the top selling album in the history of pop music, eclipsing works by The Beatles and other legendary chartbusters. Fleetwood Mac was the most popular band in the world. The secret was chemistry. The band offered a combination of the five very distinctive individuals whose talents seemed to lock into place like the gears of a machine. The rhythm section, consisting of founding group members John McVie on bass and Mick Fleetwood on drums, cold play with the power of a heavy metal band or the finesse of a light combo. Vocalist/keyboardist Christine McVie brought a dark melodicism still based a little in the blues to her work with the band. Stevie Nicks, with her classic good looks, breathy voice and fairytale princess stage demeanor, added a deeply romantic feel to the groupís sound. And finally, there was Lindsey Buckingham, the man who made the machine roll. Aside from writing many of the groupís catchiest and most commercial songs Ė "Monday Morning," "Go Your Own Way," "Second Hand News," "Never Going Back Again" Ė he played all the guitars on the albums, mixing acoustic and electric axes in fingerpicking and conventional rock stylings; did most of the vocal arrangements, which became Fleetwood Macís trademark; and had a heavy hand in the production of Rumours. And as his subsequent production work with John Stewart on Bombs Away Dream Babies and Walter Eganís Fundamental Roll showed, the Fleetwood Mac "sound" derived largely from Buckinghamís ideas about mixing and instrumental layering. But Buckinghamís genius really came to the fore with the release of Tusk in late í79. A double record set of incredible depth and scope, it was anything but the predictable follow-up to Rumours, and that was mainly because of Buckinghamís eccentric, sometimes downright bizarre compositions. The tone of the entire album was set by Buckinghamís title tune, which, much to everyoneís surprise, was a bona fide hit single like its predecessors on Rumours and Fleetwood Mac. On top of a truly strange drum beat, an almost incantatory vocal emerged from a cacophony of odd noises. The song built to a fever pitch as the USC marching band punctuated the songís second half, and Mick Fleetwood unleashed a maniacal, out-of-control drum break. Peculiar stuff, to be sure. Other Buckingham songs were equally unusual, from the rowdy, insistent "What Makes You Think Youíre The One" to the quirky "Not That Funny," to the mad rockabilly drive of "The Ledge" and "Thatís Enough For Me," to the ethereal, quiet beauty of "Walk A Thin Line" and "Thatís All For Everyone." Buckingham was not only challenging our preconceptions of Fleetwood Mac, but of pop music itself, by throwing established "rules" about song structure and mixing out the window. It was a brilliantly conceived and executed experiment, though not surprisingly, Tusk did not fare nearly as well as Fleetwood Mac and Rumours in terms of sales. Buckingham took a lot of heat for the albumís relative "failure" (though four million copies of an expensiveósome say "over-priced"ódouble album is really the equivalent of eight million records sold, not bad by any standards), but he will undoubtedly have the last laugh. Tusk is not going to sound dated in five or ten years, and I would be willing to bet that a lot more people will slowly be convinced of the albumís greatness than will forget all about it. In early December, Fleetwood Mac released itís first live album since Buckingham and Nicks joined the group. And though its pre-Christmas sales were not up to Warner Bros.í Expectations for the two-disc set, it has been selling briskly since the new year began and is getting more airplay than Tusk ever got. The reason? The "hits" are all thereó"Rhiannon," "Dreams," "Say You Love Me," "Go Your Own Way," "Donít Stop," and the list goes on. But the record isnít just note-for-note copies of the album versions. Far from it. This band rocks, propelled by the always dynamic rhythm section and Buckinghamís searing guitar leads. Once again, it is Buckingham who takes the record into the stratosphere as he rocks Nicksí "Rhiannon" into high gear with a blistering lead at the songís conclusion, turns "Iím So Afraid" into a blues tour de force with a screeching lead reminiscent of Neil Youngís "Like A Hurricane," and transforms "Not That Funny" into a bopping, shaking, and, ultimately, exploding rocker. "Monday Morning" is the perfect album opener, all kineticism and great hooks, and "Donít Let Me Down Again," an incendiary rock and roll song with definite rockabilly leanings (originally on the album Buckingham made with Stevie Nicks before the pair joined Fleetwood Mac), demonstrates the exceptional songwriting tools he brought to the band. His version of "Never Going Back Again," performed solo, backing himself up with acoustic guitar is both sensitive and charming, and "Go Your Own Way" comes across as the show-stopper it was throughout the 1980 tour. There are also three new songs on the album, which were performed live without an audience at the Santa Monica Civic. All three sound like potential hit songsóNicksí "Fireflies," which is as good as any of her better-known compositions; McVieís lovely "One More Night"; and Buckinghamís new contribution, Brian Wilsonís "The Farmerís Daughter," which originally appeared on the Beach Boysí second album, Surfiní USA. "The Farmerís Daughter" showcases the bandís harmonies at their very best; it is an inspired choice for the record. It is also a disarming way to end the album. Most live albums save the final spot for some intense rock rave-up, but "The Farmerís Daughter" rolls along like a small alpine brook, purposeful but beautifully peaceful. And instead of a sonic wash of cheers at its conclusion, a single person clapping is the last sound heard. Anyone who attended one of the tour dates from which these performances were culled knows that Buckingham has emerged as the clear onstage leader of the band. During his frequent guitar solos, he would often position himself at the lip of the stage, hunched over in intense concentration, and just wail on his Turner electric. I recall thinking that Buckingham must be a crazy man, not just because his solos were sometimes so furious that he always appeared to be on the verge of hurtling into the audience, but because after each song, after the stage lights had dimmed for an instant, I could see his eyes still rolling wildly, as if controlled by a puppeteerís hand. With the possible exception of Graham Parker and Bruce Springsteen, I have never seen a performer so wrapped up in every second of a show as Buckingham was during Fleetwood Macís two-hour-plus show. Buckingham has been involved with music for most of his life, taking up guitar at a fairly early age and always loving rock and roll and folk music. Growing up in Palo Alto, Lindsey had an older brother (later an Olympic swimmer) who turned him on to Sun Records rockabilly and the folk music of the Kingston Trio and others in the late Ď50s. Lindsey remembers loving Buddy Hollyís music; to this day he thinks of Holly as one of his primary influences. Northern Californians may remember Fritz, a band Lindsey and his girlfriend Stephanie (later Stevie) Nicks were members of for several years in the late Ď60s and early Ď70s, and which became quite popular on the South Bay steak & lobster circuit. Buckingham and Nicks put out their lone solo album (Buckingham/Nicks on Polydor) in the early Ď70sóand became stars in Birmingham, Alabama, of all places, as a result of the recordís regional popularity. The albumís producer, Keith Olsen, used tapes he made with the duo to pitch his own talents to Mick Fleetwood, and the drummer was impressed with both Olsen and Buckingham/Nicks. So much so, in fact, that when Bob Welch left Fleetwood Mac to start his own band, the Californians were enlisted to join the group and Olsen tagged to produce the first album by the new line-up. The rest, as the clichť goes, is history. On a sunny day in early December, I had the opportunity to interview Buckingham in his ninth-floor room at the Santa Clara Marriott, where Buckingham and his girlfriend were staying for the Thanksgiving holidays. (Buckingham is still close to his family, who live in the South Bay area.) Though he was still battling the flu, Buckingham definitely had his wits about him as we talked for close to three hours. Intelligent, witty, and obviously perceptive, Buckingham in casual conversation struck me as a slightly mellowed version of the dynamo I had enjoyed onstage a few months earlier. Our talk began with a discussion of the new live album, which was scheduled to be released in just three days. Q: What sorts of feelings go through you the week before an album of yours comes out? A: Not surprisingly, the feeling I have when a live album is coming out is a little different than when Iíve spent a year in the studio working on albums like Rumours or Tusk. You spend a lot of time with a record and it starts to feel like your baby. Though with a group, obviously, itís everyoneís baby. With the live album, the feeling isnít quite as tangible because I really didnít spend much time in the studio. It was more a question of assembling things that we already had, rather than building an album up from scratch. Also, I must say, Iím not really a big fan of live albums in general. How many have heard that really turned you on? Rock of Ages [The Bandís first live record], Kingston Trio Live at the Hungry i, James Brown Live at the Apollo. I donít knowóthere just havenít been many that grabbed me. A lot of groups have been putting out live albums recently and I would hate for someone to think that this just another in the pack. I donít think it turned out that way. Iím really happy with it. I initially had some reservations about doing it, but now Iím glad we did. Q: What made this the right time to put it out, aside from the obvious sales potential of the Christmas buy season? A: It sort of put a cap on the last five years of touring and recording, I think. On this tour we really came together as a band in ways that we hadnít before, and I feel that the versions of most of the songs we were playing were as good as any weíd done. I think Mick wanted us to go right into the studio to start work on the next studio record, but instead weíre taking a break, probably until May, to relax a little, work on our own projects or whatever. It feels good to have a breather for a change. Itíll allow us to be fresh when we start the next album. Q: So, in effect, the live album lets you buy a little time by keeping the groupís name out there while you rest. A: Thatís not the main reason we did it, certainly, but yeah, it does do that. We need the time off, because as great as it is to play live for people and to feel the band getting stronger on the road, itís not a situation that allows you to grow, because of the repetition in it. Itís not the same as being in the studio and being confronted with new challenges all the time that allow you to expand your horizons. Itíll be interesting to see how people react to the album. Things that we take for granted as performersólike the differences between the live versions and studio versionsóare things that a lot of people appreciate most about the group. Thatís something I donít even think about, because I can see the changes we have to make as a song evolves onstage. A song like "Not That Funny" is very different live than on Tusk, and that may surprise some people. Iíve been able to see the song grow. A lot of the songs are quite different live; others are fairly close to the studio versions. Q: The record has a much looser feel than recent live albums by other top bands like the Eagles or Supertramp. A: Well, we play a lot looser than a lot bands. That comes as a shock to some people who like our records because, in general, those are pretty well crafted. But playing onstage is completely different than playing in the studio. Also, the looseness is something thatís developed as weíve become more comfortable with each other as musicians over the years. Spreading out, giving each other more room has been sort of a natural progression for us. And thatís something, because weíre talking about a band of five individuals who have huge egos in one sense or another. Itís not one of those groups where one person dominates the whole thing, so we have to all give a little, which is healthy. By the end of the touróby the Hollywood Bowl showsóI think we were playing like a really tight unit. The shows got more rock and roll as we went along. But then I felt that Tusk was very rock and roll, and thatís the opposite of what some people thought, because in one respect it wasnít as intense performance-wise, but it was more intense attitude-wise. Q: Part of your craft in making records has been layering different guitar styles by using overdubs. Is it frustrating that you canít really re-create the subtleties of your arrangements live? A: It changes the way I play, of course. Itís been a lesson in adaptability. Being the only guitarist puts a lot of pressure on me because I feel like I canít leave any holes. But Iíve never really played with another guitarist, so Iím not really too sure of what Iím missing. Iíd like to try it sometimes. It might help me relax a little bit. Obviously you canít reproduce "Say You Love Me," which has a twelve-string and all those overdubs on it, so you try something different and hope for the best. Q: How did you happen to choose "Farmerís Daughter" for the album? A: Iíve always been a Brian Wilson fan, and so much of what heís done has either gone over peopleís heads or been ignored for one reason or another. A lot of people stopped buying Beach Boys records when Brian stopped writing about surfing, and thatís a shame. There are a lot of great Brian songs that were never hits. "Farmerís Daughter" probably couldíve been a successful single for them if theyíd released it. I think "Surfiní USA" was the only real hit from that album. But Iíve loved "Farmerís Daughter." Itís obscure enough that I thought it would be good for us to cover. I think it would be a great single. Q: Youíve mentioned that Brian was one of your biggest inspirations. Is that mainly in terms of songwriting, production . . .? A: Not really in terms of production much, thought I like what he did with the Beach Boys stuff. I admire him most as a melodic writer, an arranger, and a vocal orchestrator. When people think of Brian they think of "Little Deuce Coupe" and "I Get Around" which are great songs, but thereís also "Wind Chimes" [a bizarre tune on the largely psychedelic Smiley Smile] and all those other obscure but beautiful pieces of work. "Wind Chimes" is a classic. No one has done anything like it since. Even a lot of his later work stands up real well. Beach Boys Love You had great songs on itógreat tunes with great arrangementsóbut it just sailed over the heads of everyone and didnít sell as a result. Q: When Fleetwood Mac and Rumours came out, almost every song got airplay on AM, FM or both. I imagine the live album will also do well in that respect because so many of the groupís hits are on it. yet when Tusk was released, much of the album was totally ignored by radio. How much of that do you think is due to changes in radio, and how much to changes in the music itself? A: It was probably a little of both. There was some obscure stuff on Tusk, though obviously I thought it was pretty good. But radio has tightened up. The industry as a whole has tightened up. Take someone like John Stewart, who had a very successful album [produced by Buckingham] with two hit singles on it. He put out a follow-up album [Dream Babies Go Hollywood] that didnít do as well and suddenly RSO drops him. I donít think it would be like that at every label, but I think itís an indication of where the industry is right now. The same is true of radio. The stations attracting the broadest audiences are going to be able to charge the most for their advertising, which is the name of the game. To attract those broad audiences, the stations are going to play songs that are real noticeable, accessible stuff. Thereís no mystery about it. Tusk required more attention and a slightly different orientation to get into some of it, particularly my songs. Critically, it did very well for the most part. When people didnít like it, the criticism usually seemed to be along the lines of "How dare they put out an album so different than Rumours?" I donít think people were expecting an album like Tusk from us at that point, and the shock probably disturbed a lot of people. Some people who loved Rumours didnít know what to make of it and ended up feeling disgusted about it. But on the other hand, some people who thought Rumours was a little too middle-of-the-road liked Tusk a lot because it was more adventurous. Iím still very proud of it. Q: Several critics compared the record to The Beatles "White Album." A: I was real happy about that. Any comparison to The Beatles is a compliment in my book. Q: Actually though, I felt some of that comparison was negative, because it impliedójust as similar criticism of the "White Album" impliedóthat on Tusk we werenít hearing much of Fleetwood Mac, but rather Lindsey Buckingham fronting a band for his songs, Stevie Nicks fronting a band for hers, and so on. A: I think the "White Album" is one of the most exciting and divergent albums The Beatles ever made. By far, Revolver is probably one of their best albums in most peopleís opinions, but even then it was Paul doing Paulís music and John doing Johnís with support from the others. Theyíd been doing that since Rubber Soul, yet no one criticized those albums for that. Iím not sure itís valid to criticize something because on one record the approach is individualistic and on another itís collective. The question is, "What is the music giving off? Is it any good?" To criticize Tusk for that is silly. I think there are valid criticisms of Tusk, but thatís not one of them. Q: What are then? A: Well, in terms of songwriting, there are levels that Rumours succeeded on that Tusk didnít and vice versa. In the case of Tusk, I think itís important to think about some of the things we didnít do. We didnít harmonize very much, which was one of Rumoursí strong points. A lot of the songs didnít use full drums, and the arrangements as a whole were a lot airieróthere was more space. There were some odd combinations of instruments and sounds. If you look at a song as something that should be crafted in a certain wayóthe design of it, the way the elements are combined together in a fashion to make them accessible, to make them "hits" - then we did not succeed on that level on Tusk, and on Rumours we did. Tusk was more fragmentary, but I donít look at that as a negative thing. I think itís good because if you turn on the radio, everyone is using the same tired formulas for songwriting and recording. Q: It seemed to me that on Tusk you were tying to shake up peopleís pre-conceptions about mixing, both in the way you presented vocals, like on "Last Call For Everyone" and "Walk A Thin Line," and the way you put instruments together. A song like "The Ledge" sounds like itís just a drum and two fuzzed basses. The instrumental balance isnít what youíd expect on a conventional pop song. A: Thatís right. On "The Ledge" itís not two basses, though. Itís a bass and a guitar that has been tuned down half an octave. And that is just a snare. I did that song at my house. It sounds to me like it was put in a cement mixer and almost spat out. Itís actually one of my favorites on the album because it goes by so quickly that it almost sounds rushed, but if you try to get inside it, thereís a lot there. People are expecting to hear something else and it catches them off guard. Q: Thatís what I mean. By this stage in the game, thereís an "accepted" way of mixing drums and bass and guitars so that the relationship between themótheir relative value in a songís mixóis fairly regular from track to track, even group to group. A: That sickens me! I hate turning on the radio and being able to guess what an entire song is going to sound like in the first five seconds. I donít mean there arenít good songs on the radioóthere areóbut donít you get tired of hearing that same approach over and over again? So yes, part of the idea of Tusk was to shake people up and make them think. What is so weird about wanting to do something slightly off to the right or to the left of what people expect? I think it makes a lot of sense. Itís interesting, too, because when we go back into the studio to make our next album people arenít going to know what to expect. I like that. Weíre now in the position where we can really make something we believe in instead of what the public expects us to make. You should have a respect for your audience and appreciate their appreciation of you, but you cannot dictate your own taste through them, see yourself through their eyes, and you shouldnít be boxed into a format simply out of fear of not selling records. Q: In an interview you did with New Musical Express, you complained that some people viewed Tusk as a commercial failure, even though it sold more than four million copies worldwide. A: I remember someone saying, "God, you must be scared shitless!" before we even started doing Tusk. "How are you going to follow up Rumours?" Well, maybe Tusk was the best way to do it. We couldnít go in and make Rumours II to try to sell another 16 million records. Iím sure Warner Bros. was disappointed with the sales of Tusk. I remember reading that when Tusk came out and wasnít the big hit that everyone expected that the people at Warner Bros. could see their Christmas bonuses flying out the window. [Laughs] Thatís how they were thinking about it, and they were probably right. They hear this artsy-craftsy piece of work and they say [rolling his eyes], "Oh my God, here we go!" Iím sure they expected it would sell more. We all expected it to sell more. Not 16 million, certainly, but a couple of million more wouldnít have hurt. [Laughs] Q: How could you have expected it to sell much more if you knew all along that the LP was a great departure and not what people necessarily wanted to hear from the group? A: I expected people to be more open-minded about it, I guess. But Iím looking at it from the artistís standpoint, where itís a lot easier to move ahead and crave different things. The listening audience as a whole is probably not like that. Some feel that desire to stretch, but others have such a light surface appreciation that theyíre ready for more Rumours and really arenít the least bit interested in anything new. Maybe some of them just like what they hear on the radio and donít even know whoís in the group or what the names of the songs are. You and I are not typical music listeners. Most people donít look at music in terms of how it is innovative or how it builds upon or changes the tradition or whatever. Most people really donít care about any of that. They just want to hear a good song. But I felt that more people would be appreciative of something that, to me, sounded very fresh and unusual. Q: Even before Rumours really clicked, I remember reading that the group was planning a double LP. How much of Tusk was mapped out at that point, and how much was, as youíve sort of indicated, a reaction against doing the same old thing? A: Itís hard to separate the two. We wanted to do the double album, but Iím not sure at that point we knew what it would sound like. Speaking just for myself, it was important for me to depart and express a certain amount of individualism both as a songwriter and someone who casts a certain amount of color on the othersí songs. But we didnít sit down and say, "Hey, letís make a strange album." The evolution of the tone of the album presented itself gradually after weíd started making it. Q: What was the actual recording like? I get the feeling that it was done under all sorts of different circumstances. A: It was. A few of the songs I just did at my house. But in general, it wasnít that different than Rumours. We cut tracks, overdubbed some parts, put on the vocals. The departure, I guess, is that we had a 24-track machine in my house that I was using to experiment with different sounds and ideas. That approach, if used properly, can be really valid, I think. It becomes much more intimate. Itís more like a painter because you can respond to your intuitions, take an idea and just go with it. Sometimes itís hard to stop. It gets very, ver exciting. Because the way the studios are now, you get a couple of engineers who work a certain way and you end up working in a fairly set format. They say a chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Well, a lot of times youíll get an engineer who canít respond to what you do on all levels and it holds you back. Thereís a blockage of energy going from step A to step B. Itís fun working alone. I have about fourteen songs right now that Iíve done varying amounts of work on. I donít knowówe may all do solo albums in the next six months. Mick signed something with Warner Bros. to go over to Africa and record African drums. Heís real excited about that. Stevieís planning a record. Itís good that we have some time to think about these things. Thatís new for us. A lot of the material I was working on at the end of Tusk and what Iíve done recently is more commercial, probably, than most of Tusk, but itís still experimental in some ways. Iíve learned more about the mathematics of songwritingóhow to fit pieces together, line length, timing chords and melodies. It gets pretty complex. Q: Are you finding, though, that people have theories on what is "correct" that donít jive with your own? A: I donít talk to people about what is "correct." I think if youíre taught music in college or something, there is definitely a theory of what is correct that you can learn from. But Iíve known a lot of people who lost a lot by studying it too much. When Stevie and I were in this band Fritz years ago, the organist used to write most of the music. When he was a sophomore in high school he was writing some great tunes. Since the band broke up, he went to college and got a music degree. I was with him recently and his writing is worse now than it was then! For all his knowledge, his writing is very stiff. His training doesnít allow for any creativity. Ideally, music education should teach you about possibilities, rather than formulas. Q: Are there specific groups or sounds that have influenced you recently? Your stuff on Tusk and the live album seems slightly new wave in spirit. A: I really wasnít listening to new wave that much, but I think it did have an effect. All the new wave stuff has been real healthy, I think. So much of it accomplished what its makers set out to doógive people a kick in the ass. It was influential to me in that it made it more tangible for me to proceed with experimentation itself. It wasnít a question of hearing a good song and then trying to emulate it. It instilled a sense of courageousness in me and solidified a lot of the ideas I had about my music. Q: Has the band been totally sympathetic to your desire to explore new directions? A: It seemed so while we were making Tusk. I would be in the studio and do something and theyíd say they like it, or Iíd come in after working on a song for four or five days and theyíd never heard it, and theyíd react well. In retrospect, though, I wonder how they felt about some of my stuff. Maybe if the album had sold more theyíd be happier. [Laughs] That kind of worries me a little bit. Did you see that article in US that quoted Stevie as saying that doing the album was like being held hostage in Iran with Lindsey as the Ayatollah? [Laughs} That wasnít the feeling there at all! I mean, she wasnít even there most of the time. Sheíd come in to do her song once a week and that would be it. Hostage? [Laughs] Mick has said since then that maybe I was getting too carried away with some of my music. Itís hard for me to look at it that way. Itís weird because everyone was very supportive at the time. Q: Why is everyone dumping on you? A: Because I was the one who departed from the previously established Fleetwood Mac format. There already seems to be a little pressure to return more to that sound. I imagine, without really knowing, that our next album will represent a healthy compromise between the two approaches. We turned a corner with Tusk and now weíll turn another corner using what we learned there. Itís still too early to tell. Q: This is sort of trivial, I guess, but Iíve always wondered about the background cacophony on the song, "Tusk." Is that a tape loop of some sort? A: The drum track is a tape loop, about a 20-foot section of tape. The drum track originally was part of another song which was a lot slower. We sped the drum track up in a VSO, cut it at a certain point, and edited it into itself so we had this giant loop. Then, what we had to do was run it from one reel through the heads. But somebody had to go out across the room with something that would act like a spool to keep the loop moving steadily while we recorded it onto another machine. That was one track of "Tusk." The section youíre talking about was a live recording of the noise at Dodger Stadium when we recorded the USC Band for the horn part. If you listen closely, you can hear someone saying something like, "How are the tenors?" Itís a combination of about twelve people all talking together way in the background and then repeated over and over so it comes out as this weird noise. Q: That wasnít the first time youíd worked that way, was it? I thought "The Chain" was also assembled originally out of various bits and pieces. A: I think anyone who creates will tell you itís very difficult to work completely linearly to get what youíre after. Hitchcock, I gather, worked like that. He would totally preconceive every scene and then try to get it as close as he could to that. I do that, too, in some ways. You hear something in your head and you try to get as close as you can. At the same time, the more you work with musicóor art, for that matteróthe more you learn that you have to let the work lead you to a certain extent. I has to be give and take. You canít always be exerting your own will over a painting or a piece of music because you have to follow your own impulses and there are always gong to be a certain number of unknowns that youíll have to deal with. Iím not against planning, by any means. I think you should go into a project with as many specific ideas as possible. I just donít like to close myself off to other possibilities. Q: How much have Mick and John affected your ideas about rhythm? For instance, do you think you would be working as much with irregular rhythms if you were in a different band? A: John and Mick have affected me a lot in the past six years. Mick has an exquisite sense of rhythm. He has no idea what heís doing, technically. But heís been playing since he was ten and his drumming is totally instinctive by this point. Heís unique. Thereís a famous story about the little cowbell break in "Oh Well." Mick did that real off the cuff and then when he tried to repeat it, he couldnít do it! [Laughs] It took him a week of rehearsals to learn what heíd done in an instant. When Stevie and I joined the band our approach to music was much more classical in terms of parts fitting together and being preordained. Thatís not how Fleetwood Mac works. Itís much more spontaneous. Itís more like the Stones, in the sense that Charlie Watts is not really a technician, but he creates feelings and has an innate ability to find the right rhythm for a situation. Mickís like that. Q: But would it be your idea or Mickís for, say, the sort of counter-rhythm on a song like "Go Your Own Way?" A: That was my idea, but the point is, Mick couldnít do the beat I wanted for the song, so he did it his way. He got the general idea. A lot of my contribution to the band collectively has been as an arranger and producer. Q: Rumours is the largest selling pop album in history. Does that make you feel strange? A: Not really. I think we sort of took it for granted at the time. "Oh itís Number One again this week . . ." [Laughs] Q: How can you be blase about it? A: Because as exciting as it was, it was the music that was most important to me. The phenomenon of it selling 16 million copies far outweighed how strong the music was in my opinion, so you have to keep it all in perspective. Itís not like Rumours was "the best album ever made" because it sold the most copies. It did well for a lot of different reasons, many, Iím sure, that had little or nothing to do with the music. If Iím going to believe it sold so well because it was so great, how am I supposed to interpret Tusk selling so many fewer copies? I like Tusk better. I just canít take it too seriously. Sales are not necessarily indicative of quality. Q: Did you ever feel that your success was affecting you negatively? Did it give you a swelled head? A: Not yet! [Laughs] No, I never even put up any of my gold records. If youíre a good craftsman, a good actor, a good anything, you know you can be better and that thereís always another goal to shoot for. It seems more natural for me to keep striving, to keep learning, than to bask in the sunshine of external success. Q: When I look at bands like the Doobie Brothers and the Beach Boys and some of the other top groups, I can almost picture the "Incorporated" tag next to their names. How has as big an entity as Fleetwood Mac managed to avoid the appearance of being another corporate monolith? A: Thatís an interesting question. Iím too close to it to give you a good answer. Part of it might have to do with the whole aura surrounding the Rumours album, which was somewhat of an expose on all our personal lives. That might have added a human touch to the band that still remains. Showing some of ourselves in a very honest and succinct way might have affected the way people view the group as a whole. Another reason might be that weíve had our drummer as our manager and never had an Irving Azoff type doing it. Thatís caused problems too, because itís hard to be a player and a manager at the same time, but it might have kept us all a little more down to earth. Q: Youíve always been portrayed as a fairly private and introspective sort. How did it feel to have your personal life and your relationships splashed across the pages of half the magazines in America when Rumours became such a big hit? A: I donít feel as though it happened tome that much. The "sensationalists," if thatís what you want to call them, were always more interested in Stevie and Christine. Itís only fairly recently that writers have begun to pick up on my energy, and so far itís been pretty great. There hasnít been too much discussion of things other than my music. Iíve always been in the background more in terms of publicity or image or whatever. Thatís good. I have all the anonymity I want. I can walk about and nobody really bothers me. Q: Stevie canít, I imagine. A: Stevie wouldnít really want to. She would always dress up as flamboyantly as possible when she went out, so sheíd be noticed. Sheís a different kind of person than I am. People are appreciating me for the reasons I want to be appreciated for, and not for my chiffon gown. [Laughs] Q: What will determine whether you make your own album or not? A: It just depends on how the songs turn out. If, as a collective group of songs, itís not something Iím totally happy with, Iím not going to put it out. Iím not in any particular rush to get "my solo album" out. It has to be done right or I wonít do it. Q: Can you imagine what it will feel like to put out a record that is totally your baby? A: I think it will be pretty nerve-wracking. [Laughs[ Because you canít hide behind anyone at that point. Youíre taking total responsibility. Thatís something a lot of people who have gone solo miss. When Eric Clapton hangs out with Mick or us heís always saying, "God, I wish I was in a band again." Thatís because the burden is all on him. Itís just not the same when, as a leader, youíre paying people a certain amount each week to play with you. The balance of power is not the same, and it drains you. Bob Welch had a couple of successful solo albums, but now I think he misses being in a group where people will give you honest feedback, tell you when youíve got your head up your ass. You need that thing when other people in the band have as much at stake as you do. We could certainly all do solo albums, but that wouldnít be the death of Fleetwood Mac. There are still good creative ties and I think we all still enjoyóand needóthe feedback we get from the group situation. I canít imagine not feeling that way anytime soon. by Blair Jackson Jan 30, 1981 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||